How to Make a Documentary

When working on a script, we often think about the latest blockbuster film. But did you know you can also make a career as a documentary script writer?

What is a documentary film?

A documentary film is a film that tells a story based on real life. It is grounded in facts; the main players are people going about their ordinary lives as they happen. The characters are not actors.

Despite capturing real life as it happens, a documentary film still needs a central narrative. A narrator or a presenter usually delivers that.

A documentary film for television usually lasts between 22 - 60 minutes, depending on the desired output audience, ie TV or streaming service. A documentary film for release in the cinema would usually last longer.

The best documentaries often introduce an element of mystery and ambiguity, leaving viewers to speculate as to the full facts of the case while offering just enough to provide a degree of resolution.

Why your documentary needs a script

If you've ever watched a documentary, the chances are, it appears organic. The cameras follow the cast of characters saying what they think, and the result is pretty much a logical stream of consciousness.

However, this couldn't be further from the truth about how documentaries are made. All filmmakers have an agenda; this is not a criticism but a fact of how all stories, fiction, and non-fiction, are constructed.

The filmmaker wants to tell a specific story. To do that, they must have an idea of where they are going, which means it needs a script.

This doesn't mean you will put words into your interviewees' mouths. Instead, the script includes a voice-over or piece to camera deliveries and a list of b-roll footage.

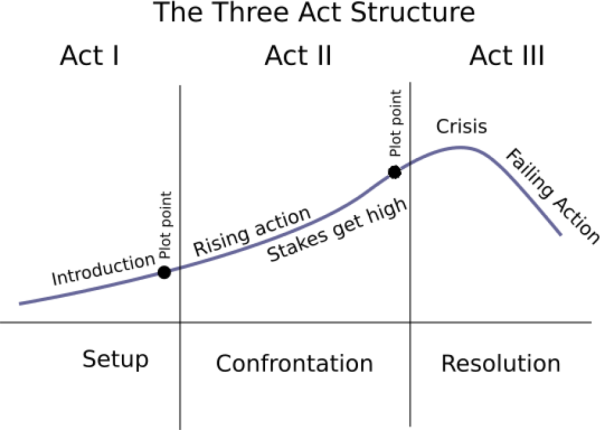

Remember, a documentary must still adhere to a three or five-act structure (see three of five-act document at the end of this section) like a fictional film does. Having a script can help you more clearly see this structure.

How to find your story/idea

Before you begin shooting your script, you need to know where it will go: a structure (see three of five-act document at the end of this section). You must first decide on the scope of the shoot. Where are you going to shoot? For how long? And who will the main protagonists be? In other words, who will we be positioned with throughout the script?

These ideas may change as you start shooting, and you may have to adapt by extending the shoot, spending more time interviewing, and following someone who you previously thought would have a lesser role in the film.

To come up with these ideas, start by considering what interests you. For example, what areas of life fascinate you? And then think about how you might be able to tell a compelling story from that.

It would help if you also balanced those questions with what is possible. You may be interested in the inner workings of politics, but if you've never made a film before, you are unlikely to be granted access to the White House. You could, however, approach your local town council about doing a documentary series about what it's like to work there.

How to create a documentary film treatment

Before you write your script, you must first write a documentary film treatment (see bottom of page below). This serves almost like a plan for your documentary script and enables you to gather your ideas first.

The film treatment should be between 10-14 pages long. It should contain a summary of your idea with the narrative and main cast of characters. It should include the film's proposed length and aim to keep the readers involved.

Think of the work that goes into a fictional script: the detailed description of characters and their surroundings, and be sure to write in a similar style.

How to structure a documentary script

Once you've written your treatment and work has begun on shooting key scenes and characters for your film, you can now start your script.

The script's purpose is to show how all the different components of the shoot come together to form the film. These are the shots and interviews married alongside the b-roll footage and the narration, either a voice-over or pieces to camera.

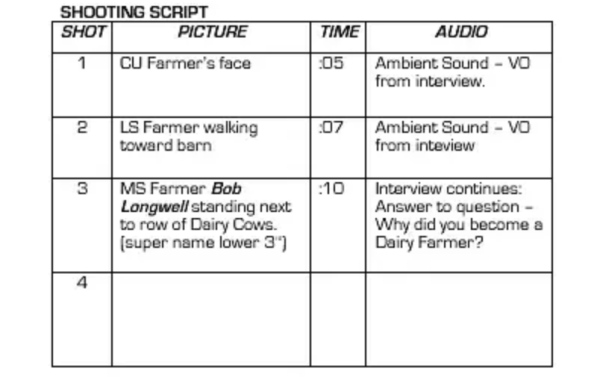

You should divide the page into three columns, one listing the scene number, one focused on video, and the other on audio. Anything the viewer sees during the scene should be recorded in the video section, such as on-screen captions, camera angles, and b-roll footage.

A documentary shooting script should be split into three columns: picture, time and audio.

The audio column should include anything the audience will only hear: specific songs, voice-overage footage, or dialogue.

You can generally only work on your script after collecting your interviews, gathering your data, and doing extensive research. In that sense, a documentary script is written much later than a script for a film or TV series.

How to format a documentary script

In general, you should try to follow the one page per minute rule when you write a documentary script though this can be hard to follow if you have many different scenes.

Use size 12 font and courier.

How to write a documentary script step-by-step

Writing a script for a documentary film is a different experience from writing a movie or TV series set in a fictional world. But hopefully, this blog has helped you not be overwhelmed by the process. There is a step-by-step plan you can follow to make it easy.

Screenwriting Battle: 3-Act vs. 5-Act Story Structure

Ah, story structure.

Many storytellers face a dilemma when they embark upon their quest to begin constructing a narrative is how exactly they want to structure the yarn they wish to spin. Ultimately it comes down to personal preference and how your brain is wired to the telling of tales, but here are two of the more popular versions of story structure and how you might best use them to scaffold the beats of your next screenplay: 3-act story Structure and 5-act story Structure.

Three-Act Structure

The notion is a simple one; your story is divided into three sections.

Act I – Beginning -Thesis – Set Up

This is where you introduce an audience to your protagonist, ask the piece's dramatic question(s), and establish theme and tone. You also construct the rules of your world and outline the stakes.

Act II – Middle – Antithesis – Confrontation

This is the longest and densest part of any narrative. Many a good writer stumbles in the quagmire, which is Act II.

The protagonist usually isn't having a good time either. Usually, at this stage of their journey, they're being tested at every turn on their way through the trials and tribulations which are being thrown at them.

This is also where you'll start exploring the B and C plots peppered throughout your work.

The 5 Act Structure mixes this part up a little, but we'll get to that later.

Act III – End – Synthesis – Resolution

If our hero is going to live happily ever after, this is where they get to do it. Antagonism(s) will be defeated, love interests will be swept off their feet, and the world will be put back in order.

The dramatic question introduced in the first act is answered, and all subplots conclude.

3-Act Story Structure

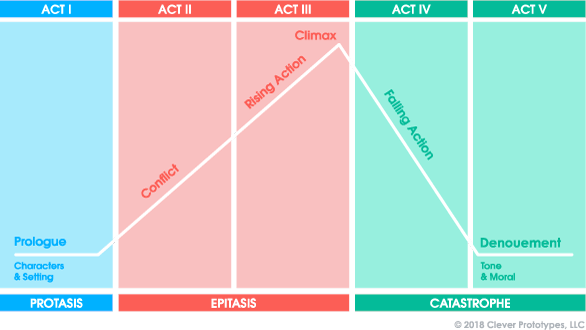

Five-Act Story Structure

What is the Five-Act Structure?

So, what's the appeal of the 5-act script structure?

First things first, a 5-act story isn't usually any longer than a 3-act story structure. All you are doing is simply breaking down the rather tricky bit in the middle of your arc.

This is the story structure favored by English playwrights, renowned dramaturg, and the scourge of schoolchildren everywhere: William Shakespeare.

Act I – Once Upon a Time

It would feel silly to start anywhere else. This is a space of comfort for your protagonist. One day, they are invited to go on an adventure and are ripped from their comfort place and forced to evaluate who they are in increasingly different ways.

Act II – Physical Transformation

During Act 2, the stakes of the story are all physical. The protagonist might alter their appearance, journey to a new area, or gather their equipment in the face of the challenge awaiting them. Currently, that is merely as far as they are willing to go to solve their problems.

Act III – Emotional Investment

However, just trying on a new outfit and pumping iron for a bit doesn't quite get them what they want. So, they have to consider how they feel about this new version of themselves.

At the midpoint, which comes during this act, they will experience an enormous outpouring of their newly discovered emotions juxtaposed by a moment of extreme rejection. Our protagonist will then think about abandoning their newfound identity for a beat or two but will double down on their efforts and continue moving forward.

Act IV – Psychological Examination

Now our protagonist has to dig deeper into their psyche and understand why they needed to go on this journey in the first place.

They will ask big questions of themselves like:

Who do I want to be? Where am I going? What is it that I'm destined to become?

Act V – Spiritual Transformation

Finally, all our protagonists (s) need to prove that they have been on this journey by being challenged to showcase this new version of them. This lets an audience know that the protagonist has genuinely changed, and the shift will stick long after the screen fades to black.

5-Act Story Structure

Summing Up the 5 Act Structure

The best thing about studying screenplay structural writing is learning that these two paradigms aren't the only way that you can break a story down. There are so many methods — some so unconventional that perhaps you've never heard of them.

When you are approaching your writing, it's all about using the tools that you find most useful and refining them to fit your style and the needs of the project you're working on.

Some of you will find the 3-act story structure a natural fit, whereas others wouldn't dream of using anything other than the 5-act structure. Or, perhaps you would prefer to use an entirely different screenplay structure! The key is to experiment and figure out what works best for you. Play with both structures and see which suits your sensibilities best.

Always remember to keep your story moving forward, your characters engaging, and your themes truthful. The structure is always second to storytelling.

How To Write a Film Treatment in 5 Steps

Writing film treatments can be complex. It isn't the same as a synopsis or an outline, though it may serve as each of those. A treatment in the film industry is utilized for a variety of reasons and can be an essential part of the process of developing an idea. So, what is a treatment, how do you write one and why are they important?

What is a treatment in screenwriting?

The film and television industry doesn't have a standard definition of what "treatment" means. For example, if someone asks you for treatment, they could mean a two-page overview or a thirty-page document, basically the script without the dialogue.

However, film treatments are generally defined as a summary of a TV show or film. A treatment should contain all the essential elements of the story, including scenes, themes, and the project's tone. Film treatments can also be referred to as story treatments.

As you approach writing a treatment, for any reason, here are a few tips that will help.

Six critical elements of a film treatment

While each treatment may differ a bit, generally, your treatment should contain:

-

Title of story

-

Name and contact information of the writer

-

Logline (brief description)

-

Key characters

-

Summary of the story

-

Additional information about the themes and tone of the projects

Now that you know the generalities let's dive into the details.

Why are film treatments necessary?

Learning how to write a film treatment is essential for the emerging screenwriter. Often, producers and executives want to check out your story before signing a contract with you. Film treatments are an excellent way for you and producers to save time and energy on projects. Thus, being able to write an excellent film treatment could be what stands between securing you a job!

So, how do you write a film treatment?

How to write a film treatment in 5 steps

1. Decide the type of document you're creating

Make sure that you understand your goal in creating the treatment. For example, is it to serve as a pitch document for others? Or is it so you can explore the story you're prepping to write out as a script?

Having a solid sense of the target will help you decide what the treatment will look like. For example, a treatment for others may need to spell out a bit of the feeling or mood that you would otherwise keep in your head. However, a treatment for yourself may not have to be as precise, so long as you understand what you meant when you refer back to it.

2. Decide on the length

This is largely determined by the decision mentioned above, knowing the length will help dictate how you write.

A one or two-page document can be great to get a sense of the project, but it means you'll have to paint pretty broad strokes at the risk of being too general.

A longer document can get into the details, but of course, it will take longer for others to read. And sometimes those details themselves can get in the way of the purpose of the treatment, where all you'll see is trees but no forest.

Deciding on the length ahead of time can give you a target to aim for. You may be a little off in the end, but that's okay.

3. Don't include everything !!!!!!!!!

There's a reason that the treatment isn't the script. It can't include everything, and it isn't very smart to try. Sometimes this means little bits that will show up in the margins of the scenes getting cut from the treatment, but other times it will mean whole subplots.

When deciding on what to include and what not to include, ask yourself if evaluating is essential to understanding the protagonist's journey. If it's not, it may be best to leave it out of the treatment.

That being said, as you're first drafting your treatment (and yes, I said draft, because just like a script, you will revise this!) when in doubt, include it. So it's easier to trim something out if it's there from the start.

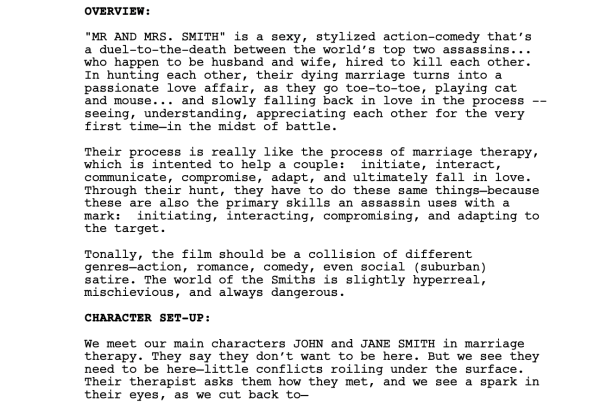

Mr. & Mrs. Smith

4. Write it in proper prose

Screenwriting format is not proper prose, and while this is helpful for what we do in scripts, it can sometimes feel a bit like the scraps of a language that isn't fully codified. By sticking with correct grammar and syntax and the like with your treatment, your technical writing will have a stable base and allow you to focus on what's crucial in the treatment: the story.

Screenwriting isn't just telling what happens but also how we see and hear what happens. A treatment isn't supposed to worry about the latter, which is why writing it in proper prose is a good idea. Additionally, it's easier on readers.

5. Just tell the story

Writing a treatment, regardless of the reason (for you, for others, for fun), can bring up as many problems as writing a script. So, for example, if you think about the treatment as simply telling the story to friends around a campfire, it can help get you out of your head.

The best thing you can do while writing your treatment is to write without the delete key. It is always easier to edit a written document than belabor a blank page.

Write as if you can't look back, just telling the strokes of the story piece-by-piece, and then go back and edit what you need.

BONUS TIP: Don't include dialogue

Feel free to ignore this one, but it's something that I do in my treatments, and since I started doing this, I've found it helpful.

If you include lines of dialogue, even a few, it can start to blur the line between treatment and script. For example, keeping a hard and fast rule of not having a conversation is great to force your brainpower on the story.

That doesn't mean I don't explain the dialogue. But I'll write something like, "Jack explains that he's not there for the money" instead of writing, "Jack says, 'I'm not here for the money!'"

It's a slight difference, but throughout treatment, it helps and forces me to only talk about the dialogue when necessary.

Save that masterful dialogue for the script itself.

Film treatment examples

To help give you more of an idea of what professional film treatments look like, let's take a look at a few different treatments.

Additional reading: "scriptments"

Scriptments are a hybrid between a treatment and a script. Once they have written their treatment, some writers want to add more information, such as snippets of dialogue.